CITATION

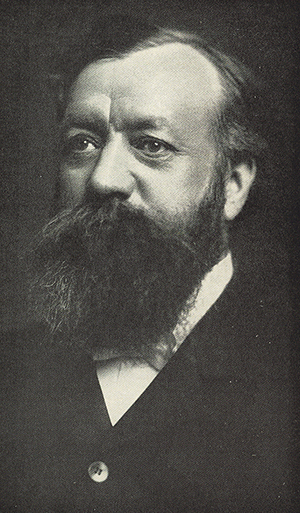

Newton Horace Winchell (1839-1914)

Minnesota’s Geologist

2021 ILSG Pioneer

Newton Horace Winchell was first director of the Minnesota Geological and Natural History Survey at the University of Minnesota from 1872 to 1898. During his 26 year tenure, Winchell and his staff visited every corner of the state to document its bedrock geology, mineral deposits, quarry stone resources, glacial deposits and landforms, paleontological record, modern flora and fauna, and hydrologic framework. The survey’s findings were recorded in 24 annual reports, which summarized each year’s accomplishments and commonly totaled hundreds of pages, and in a six volume final report. Pdfs of these reports are all available from the University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy (https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/708).

As skillfully told in Sue Leaf’s 2020 engaging and intimate biography of Winchell’s private and professional life, Newton Horace Winchell (NHW) was born and raised as the middle child in a large family near the New York-Massachusetts-Connecticut borders. At the age of 15 after 8th grade, he began teaching in small schools in the area. In 1857, he moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan to live with his older (by 15 years) brother Alexander, who was a professor of natural history at the University of Michigan and director of the Michigan Geological Survey. Over the next 12 years, NHW worked as a teacher/principal in various southern Michigan towns, got married, had two children, and also intermittently took classes at the U of Michigan. In the summer of 1860, he was hired by the Michigan Geological Survey as a botanist and explored the coastlines of Lakes Huron and Michigan. NHW completed his BA degree in 1866, committed to geology as a profession, and began to work more regularly for the Michigan Survey. In 1869, he completed his MS degree at U of Michigan and became Assistant State Geologist under his brother. In 1870, the Michigan legislature defunded the geological survey, which prompted NHW to work the summers of 1871 and 1872 for the Ohio Geological Survey under the direction of John Newberry. In July 1872, University of Minnesota president, William Folwell, offered NHW the position of director of the newly created Minnesota Geological and Natural History Survey. With an initial legislative appropriation of $1000 per year, Folwell estimated that the survey would need 20 years to accomplish its task of conducting “a thorough geological and natural history survey of the State". In addition, he would be responsible for teaching two geology courses each year and organizing a natural history museum. NWH accepted the offer, and began field work that fall.

The first five field seasons of the Survey (1872-1877), NWH and his small staff focused their attention on the geology, geomorphology, paleontology, and economic geology of southern Minnesota counties. In 1876, Winchell’s responsibility for organizing the University museum was assisted by the hiring of Clarence Herrick. HNW’s other non-survey obligation of teaching college classes was removed just before the 1879 field season by the hiring of zoologist Christopher Hall, who was also appointed assistant director of the survey. Additionally significant hires in 1879 were those of glacial geologist Warren Upham and paleontologist Edward Urlich. Although NHW was well versed in both these disciplines, their contributions and other staff hires in the 1880’s, freed Winchell to devote many months of field work per year over the next decade and to accomplish his most challenging task –deciphering the Precambrian geology of northeastern Minnesota.

The Paleozoic, Cretaceous and Quaternary geology of southern and western Minnesota was summarized in Volumes 1 (1884; 673 p.) and 2 (1888; 671 p.) of the final report written by NHW and Upham. The paleontology of Ordovian and Cambrian rocks (at the time interpreted to be Upper and Lower Silurian) and of Cretaceous rocks was summarized in the 1200+ page Volume 3 that was published in two parts (Pt. 1 - 1895; Pt. 2 - 1897).

The task of mapping and deciphering the Precambrian geology of northeastern Minnesota started in the summer of 1878 when NWH and three others explored the Lake Superior shoreline from Duluth to the Canadian border by Mackinaw boat. In all, they collected over 300 samples. Then, from September to November of that same year, NHW and two Ojibwe guides paddled and portaged from Grand Portage, to Lake Vermilion, down the Embarrass, St. Louis and ultimately the Mississippi rivers to Minneapolis – a 700+ Km trek! Winchell devoted most of his remaining field seasons to northern Minnesota geology with the able assistance of his son (Horace), his son-in-law (Uly), and his brother (Alexander). With iron mining taking off on the Vermillion Range (1st ore shipped -1884) and then the Mesabi Range (1st ore shipped - 1892), much of NHW’s attention was focused on that geology. Also, beginning the mid-1880’s, Winchell regularly employed petrography to better understand the granite, gabbros, greenstones, and basalts that he encountered. In fact, in 1895, he took a year-long “sabbatical” to Paris to learn petrographic methods from the French petrographers LaCroix, Fonque and Michel-Levy. Still, as I highlighted in an ILSG talk in 2004, Winchell struggled mightily to understand the genesis of Precambrian crystalline rocks. In the introduction of Volume 4 of the Final Report (1899), wherein he summarizes his studies of northern Minnesota geology, NWH comments: "Here [among the crystalline rocks] the geologist is deprived of his usual guides and guys, and finds himself floundering in a muddy sea of innumerable conflicting currents".

Some other notable aspects of Winchell’s remarkable career include his role in the development of the first scientific journal exclusively devoted to geology – The American Geologist. He served as its managing editor and publisher from its inception in 1888 to its merger with Economic Geology in 1905. Part of his motivation for creating this journal was to give a voice to state survey geologists which had the potential of being dismissed by academics and experienced overreach the USGS. Also, as a founding fellow, NHW was instrumental in the creation of the Geological Society of America, also starting in 1888. After the Minnesota survey ended in 1899 and he got closure on Volumes 5 (1900, Uly Grant’s PhD thesis) and 6 (1901, atlas of county geologic maps), NHW focused the final decade of his life on archeological studies with the Minnesota Historical Society, particularly as they applied to native peoples who lived in the midcontinent before, during and after the last glacial episode. He published Aborigines of Minnesota in 1911 (743 p. 642 figures, 32 plates). As Sue Leaf points out, this well received book was “comprehensive in scope, methodical in approach, and meticulous in detail; a worthy companion to the voluminous Geology of Minnesota.” Winchell died on May 2, 1914 due to surgical complications at the age of 74.

Newton Horace Winchell’s geological survey took the blank canvas of Minnesota’s landscape and began the process of revealing the rich diverse geology that we now recognize and continue to embellish and improve upon. As Sue Leaf’s book proclaims in its title, Newton Horace Winchell indeed deserves the designation as “Minnesota’s Geologist” and as one of the great pioneers of Lake Superior geology.

Jim Miller